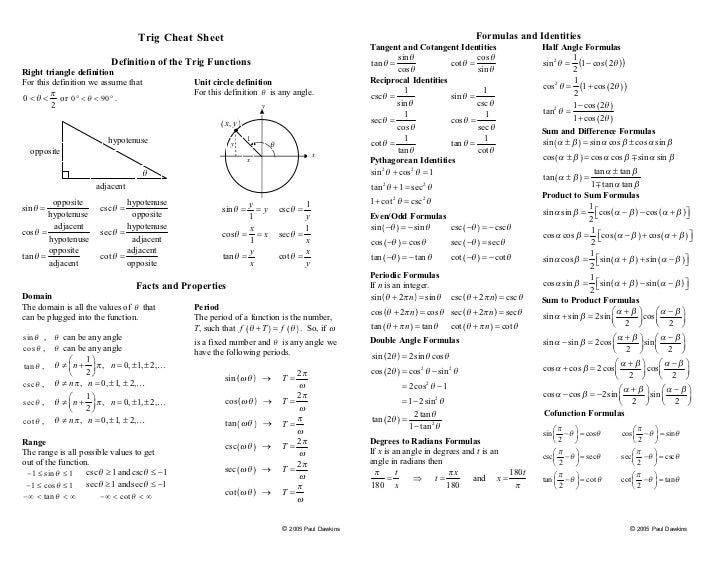

When working with right triangles, sine, cosine, and other trigonometric functions only make sense for angle measures more than zero and less than π / 2. A simple demonstration of the above can be seen in the equality sin( π / 4) = sin( 3π / 4) = 1 / √ 2. It may be inferred in a similar manner that tan(π − t) = −tan( t), since tan( t) = y 1 / x 1 and tan(π − t) = y 1 / − x 1. The conclusion is that, since (− x 1, y 1) is the same as (cos(π − t), sin(π − t)) and ( x 1, y 1) is the same as (cos( t),sin( t)), it is true that sin( t) = sin(π − t) and −cos( t) = cos(π − t). It can hence be seen that, because ∠ROQ = π − t, R is at (cos(π − t), sin(π − t)) in the same way that P is at (cos( t), sin( t)). The result is a right triangle △ORS with ∠SOR = t. Now consider a point S(− x 1,0) and line segments RS ⊥ OS. Having established these equivalences, take another radius OR from the origin to a point R(− x 1, y 1) on the circle such that the same angle t is formed with the negative arm of the x-axis. Because PQ has length y 1, OQ length x 1, and OP has length 1 as a radius on the unit circle, sin( t) = y 1 and cos( t) = x 1. The result is a right triangle △OPQ with ∠QOP = t. Now consider a point Q( x 1,0) and line segments PQ ⊥ OQ.

First, construct a radius OP from the origin O to a point P( x 1, y 1) on the unit circle such that an angle t with 0 < t < π / 2 is formed with the positive arm of the x-axis. Triangles constructed on the unit circle can also be used to illustrate the periodicity of the trigonometric functions.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)